Interview Series: Eric Benhamou

A rare and reflective discussion with the legendary tech entrepreneur and investor.

This month interview is another tech legend and yes, it’s definitely displaying the talents (not just from France) from immigrants making Silicon Valley what it is. Eric and I met back in the late 90s/early 00s. I was working for Metrowerks and we were tasked into making tools to develop apps on this neat device from USRobotics. Little did we know that it will become the legendary PalmPilot which started the smart mobile devices revolution.

So who is the ever low-profile but driven Eric Benhamou? Born into a vibrant Sephardic Jewish family from Toledo, Spain, Benhamou's journey from Algeria to the United States is nothing short of a global adventure. After fleeing Algeria in 1960, his family settled in Grenoble, France, where he grew up, dazzling everyone as the youngest graduate from École nationale supérieure d'arts et métiers. At 20, he took his talents to Stanford and earned a Master's degree. Benhamou’s career skyrocketed as he co-founded Bridge Communications, led 3Com to Fortune 500 glory, and revolutionized the tech world with the PalmPilot. Not just a tech wizard, he co-founded ISRAEL21c and Israel Venture Network, taught at INSEAD, and now drives innovation with Benhamou Global Ventures. With accolades like the Nessim Habif Prize and Ellis Island Medal of Honor, Benhamou’s story is one of relentless ambition and a touch of global flair!

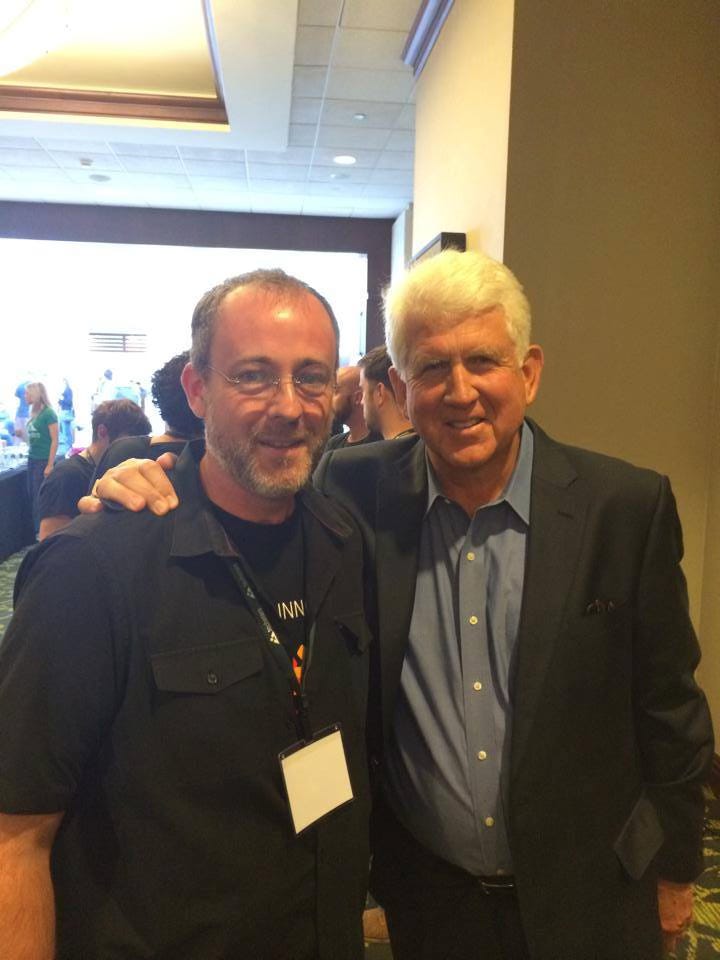

And the reason I was able to gladly interview him was because his VC firm hosted a discussion among 2 other tech legends who have also been interviewed on this Substack. How many times can you see Marylene Delbourg-Delphis, Jean-Louis Gassee and Eric Benhamou in one place? Right there, you have so much of the heart and brain of Silicon Valley History.

I hope you will enjoy Eric’s answers as much as I did. He gracefully answered all of them with a unique personal and sometimes vulnerable angle showing he is one of the authentic personalities from the tech world.

The Delivery Man (DM): Can you tell us about your early life in Algeria and how it influenced your approach to creating new roots in a new place many times?

Eric Benhamou (EB): The early years I spent in Algeria were years of upheaval for the country. The winds of Algeria’s independence from France were blowing hard. I remember moving multiple times. When my family was living in Alger, my house was bombed. Then my school was bombed. I remember walking home from school with my handkerchief on my face to protect my eyes from tear gas. We eventually packed and left everything behind when I was 5. We moved to France. Other relatives moved to Canada or Israel. It was a complete reboot. This experience of dealing with real danger, with civil war, and with the trauma of transplantation were formative for me. It made risk-taking a very normal way of life, as well as immigrating, restarting and adapting. Had it not been for this early experience, I would not have packed my bags again at the age of 19 and re-booted my life in the US.

DM: How did your experiences in France shape your interest in technology and engineering?

EB: By a happy coincidence, 1972 was the first year when my Engineering School (The “Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts et Métiers”) acquired a mainframe computer. It arrived a few weeks after I had started my freshman year. It was an IBM 1130, the classical mainframe that you see in movies filmed in the 60’s and 70’s. It came with punch card stations, rotating hard drives and magnetic tape backup units. It also came with an IBM operator named Lydia, who in addition to being a pleasant and attractive young female in a boys school, was the only person who knew how to operate the unit. I developed a fascination for the school’s data center and spent many late nights there pouring over the manuals and discussing their content with Lydia. I soon became one of a handful of self-taught students who alone, knew how to program and operate the mainframe and its peripherals, which gave me a certain guru-like aura. I was a 17-year-old hippie at the time. I was not doing drugs, but I knew how to program in Fortran and Cobol. This put me in a top 1% category in my school.

The following year in 1973, another experience added to my fascination with computers: a fellow student showed up in our structural engineering class with an HP-35 programmable calculator. His father got it for him during a business trip to the US. This student aced all his exams, finishing the tests 15 minutes before all the other students who were toiling on calculations with their slide-rule. He was kind enough to let me play with it, and I soon realized that the same complex calculations which took me days to program on the IBM mainframe could be performed much more easily with the handheld HP calculator, thanks to the power of microprocessors. I read about HP and learned that this American company was started in Palo Alto by two alumni from Stanford university.

These two early encounters with computer technology set me on an irreversible course to go there and experience it for myself.

DM: What motivated you to pursue higher education in the United States, and how did your time at Stanford influence your career path?

EB: I arrived at Stanford in the mid 70’s, 2 years after the invention of the microprocessor, 6 years after the Arpanet (the precursor of the Internet) had begun switching packets (using protocols invented by Vinton Cerf) between UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute, and 2 years after Bob Metcalfe at Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) had invented the Ethernet local area network. In other words, this was ground zero of the Information Technology era and ground zero of the Silicon Valley that we know today. I could have missed it, had I been born a couple of years prior, but people (mostly males) born in 1955 were particularly fortunate. I have this in common with Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Eric Schmidt: we are all born within a few days of each other: a lucky year and a productive vintage. Malcolm Gladwell made that insightful observation in his books “Tipping Point” and “Outliers”. Being at the right time in the right place gives you an incredible head start.

The Delivery Man with Vinton Cerf

The Delivery Man with Bob Metcalfe

DM: Were there any significant challenges you faced as an immigrant in the tech industry, and how did you overcome them?

EB: Surprisingly, I faced very few challenges as an immigrant in the tech industry. Language was not a problem for me. I had mastered English a long time before arriving in the US, and had aced my TOEFL test in my Stanford application. Culturally, I felt comfortable and welcomed by my colleagues and professors. Furthermore, at the time (this was several decades before DEI), the environment was truly a color-blind meritocracy. It really did not matter where you came from or what pigments defined the color of your skin, as long as you had the right skills and competences and were willing to work hard. On this score, things have unfortunately changed significantly…

DM: Can you share a memorable moment from your early career that had a lasting impact on you?

EB: In 1981, about a year after we had received our initial venture funding at Bridge Communications, I flew down to UCLA (our first customer) to install our communications servers and routers in the Computer Science department of the university. It was during the winter break. We were putting all the computers of the department (mostly DEC PDPs, VAXes, Data General Eclipses, etc..) on a common Ethernet local area network, having beaten DEC, IBM and other big vendors. But the system had to work flawlessly before the students got back from their break. It was a trial by fire. It could easily have failed (which would have had potentially very dramatic consequences), but thanks to the valuable help I was receiving over long phone calls from my colleagues still at the home base in Cupertino, I managed to make it work “in extremis”. This set us on a path to success at Bridge, as UCLA became our flagship reference account. The combination of pressure, mental stress and exhilaration I experienced in this marathon first customer deployment captures the unique emotions that many entrepreneurs feel at this stage (the ultimate moment of truth). This is the “high” that they all thrive on.

DM: Let’s shift to your successful career as founder and captain of industry. What inspired you to found Bridge Communications, and how did you identify the market need it addressed?

EB: After a few quarters in graduate school at Stanford, I realized that the last 2 years of a PhD program in Electrical Engineering or Computer Science were not terribly useful. You had completed the research and mastered the subject of your quest, but you had to publish a few papers, get the blessing from your thesis advisor, and coast for a few quarters advising undergraduates. So I decided to drop out of my PhD program and satisfy myself with a 2nd Masters degree. After a brief stint at Cromenco, I decided to join a well-heeled startup called Zilog, led by Federico Faggin, the co-inventor of the microprocessor (while he was with Intel). “Well-heeled” because it was backed by Exxon, whose Office Systems division charter was a deliberate and valiant attempt of the oil giant to diversify its business. I was attracted to Zilog which at the time was building and selling the Z80 microprocessor, alongside full-fledged microcomputer systems like the MCZ. My task was to help flesh out the line of Z80-based systems by showcasing powerful applications. A good example of this line of work was to replicate the modern office environment that Xerox PARC had developed in the early 70’s, using Zilog components. So, my colleagues and I created bitmap displays with mice, workstations, print servers, and file servers, all connected on a local area network which we branded Z-net. Z-net was essentially an Ethernet LAN built out of Zilog components, using the same fundamental media access method (called CSMA/CD for carrier sense multiple access with collision detection). Frankly, at the time, I had no notion of a “market” for this technology. It just felt extremely cool and fun. I simply had a vague but powerful conviction that all computers were meant to be connected across both local and wide area networks in order to share information and other resources. It seemed inevitable that in the next wave, our common challenge was going to be to build a vast, reliable, global network, and for this task, a key ingredient was the emergence of standardized protocols of communication.

DM: As the CEO of 3Com, what strategies did you implement to drive the company's growth and success?

EB: In my early years as CEO of 3Com, I remained an engineer and an entrepreneur at heart. I was not a businessperson. I had limited understanding of what marketing people and business consultants could contribute to the business. I probably had less patience too. I continued to follow the instincts I formed in my days at Zilog and Bridge: the world’s computers needed to be connected and 3Com was going to create the architecture and the products to do so in the simplest, most effective way possible. I called this strategy GDN for Global Data Networking. I still have an old corporate T-shirt printed in the late 80’s that says, “Ask me about GDN”. I keep it as a piece of memorabilia from my geek days (DM side note: someone probably picked up this T-shirt from a Goodwill store without knowing the historical significance of it.)

DM: Can you discuss a pivotal decision you made at 3Com that significantly impacted the company's trajectory making it a cornerstone of the “smart” devices revolution?

EB: The most impactful strategic decision I made in 1987 was to proclaim that we were going to become a full networking company, not a computer company. The nuance may seem subtle when one thinks about this distinction today, but in the 1980’s, the line was very blurred: computer companies like IBM, DEC, HP and others were all building networks, and networking companies like 3Com were also building workstations, print servers, file servers and network operating systems. At that game when every player is trying to build everything and declare it its own walled garden, the biggest player would inevitably win over time. I decided we needed a singular focus. We could not be both a computer vendor and a networking vendor. Some companies like Sun Microsystems (who started at Stanford while I was a graduate student) were meant to become a computer company. We at 3Com had a networking DNA. I decided we should only build networking equipment, and we should use open standards for networking protocols, such that customers would remain free to use any type of computer that they wished. We take it for granted today that anything/anyone can speak to anything/anyone over the internet, but it all stems from this fundamental decision, which impacted not only the trajectory of the company but of the entire industry. Today, when I walk into a conference room or an airport lounge and connect my laptop or smartphone to the local Wifi, I think to myself that had we not led the standardization of an open Wifi protocol based on Ethernet, the world would be a far messier place than it is. In the words of Steve Jobs, we “made a dent” on the planet.

DM: What do you consider your greatest achievement during your time leading 3Com, and why?

EB: Interestingly, what comes to mind is not the long list of technology inventions and patents credited to the company, nor the twenty-fold share price increase that our investors enjoyed in the 90’s. Rather, it is the fact that after the seminal decision made in 1987 to become a full-fledged global networking vendor, we transformed the company from a 500-person startup in Silicon Valley into a 25,000 global enterprise with a presence in over 100 countries around the world, unified by a very strong, respectful, merit-driven culture. I believe that to this day, 90% of 3Comers look upon their years at 3Com with fondness and pride, not only because they were all option holders and made a fair amount of money, but because their work had meaning. After all, most of the first billion humans who connected to the Net in the 90’s did so with 3Com products.

DM: How did your leadership style evolve over the years as you transitioned from founder to industry leader?

EB: In my early years as a leader, I looked at the world through the eyes of an engineer. I was obsessed with details and expected everyone to do what they said they were going to do. As I matured in the role, like many, I became far humbler and more tolerant. I stopped micromanaging, became a good listener, and became able to relate to people very different from myself. As I transitioned to my current role as a venture capitalist, what became even more important was to maintain a curiosity about new ideas and an ability to question my own beliefs and models.

DM: What motivated you to shift from leading companies to becoming a venture capitalist?

EB: Serving as CEO of Fortune 500 company in a hard-charging industry took a toll on me and my family. I made a personal commitment to my wife at the time that I would not stay in the role past December 31st, 2000. This has nothing to do with Y2K superstition, but this date was a natural milestone. I also have the belief that leaders often overstay their welcome and stay in their job past their prime. I shared this intent to transition with my board and gave them several years of notice. When the time came, I did not renege on my commitment, but I had not yet figured out what to do next. At the age of 45, I felt way too young to retire. I started serving on a few boards, but this was not entirely satisfying. It was far too removed from the action, and I missed the days when I could interact with my engineers and touch (almost physically) how technology was invented, and products were developed. This is how I started to dabble in angel investments. BGV started off as my family office in 2003 and was the vehicle I used to meet entrepreneurs and help them with their business. I was very motivated to engage with new generations of founders, and be a resource to them to help them build better businesses.

DM: What qualities do you look for in entrepreneurs and startups when deciding to invest?

EB: I have a favorable bias towards immigrant entrepreneurs (see related post on this Substack). I was one myself, and I know that the immigrant experience forces you to make tough choices, to leave everything behind and transplant yourself and your family and risk it all for an uncertain future. Anyone who fares well through this journey is mentally prepared to face the stress that awaits them as an entrepreneur. Clearly, one does not have to be an immigrant to be prepared for the entrepreneurial experience, but I look for people who have traversed a personally challenging phase in their lives and come out of this experience stronger.

It may surprise you that the other quality I look for is not intelligence. Smart people are a dime a dozen. It is hardly a differentiator, particularly in Silicon Valley. Rather, it is table stakes. I look for individuals who are fundamentally earnest: people who do what they said they were going to do. I pick up simple clues such as being at an appointment on time, being responsive to questions over email, answering questions precisely and honestly. Being earnest and dependable does not mean being rigid and closed to change. I know that the business plan that I fund at seed stage or series A is not the one that the company will end up executing. There will be multiple tumbles and pivots along the way. Knowing when to stay the course and knowing when to change is the ambiguity that entrepreneurs must navigate. Both require integrity and self-knowledge. These skills are essential to become a successful company builder. This is probably at the polar opposite to the well-known Silicon Valley mantra “fake it until you make it”, which epitomizes the hubris and excesses of the local culture.

DM: Which current tech trends or emerging technologies are you most excited about, and why? If AI, please elaborate :)

EB: My partners and I have been excited about AI for at least 10 years, a long time before the world discovered in amazement the experience of interacting with ChatGPT. We are an AI early adopter/believer and have the full conviction that this invention is as seminal as the ones I encountered as a young graduate student at Stanford in 1976: microprocessors, Arpanet, Ethernet, etc… As usual, we are probably all overestimating what impact this wave of technology will have in the short term, and underestimating its impact in the medium and long term.

From an investor perspective however, not everything AI is worth investing. Unlike in my days as a young entrepreneur, there are now several extremely well-capitalized and well-run technology companies making mind boggling investments in various aspects of AI. We should not think that our modest venture capital firm, however proud I am of it, could compete with these giants. So, we will not invest in fundamental large models, or the next generation GPUs or TPUs. We are happy to leave this to others. Our investment approach is far more solution oriented. We like to back companies which use AI, combined with high quality proprietary data sets, to power a solution that will make an enterprise far more productive and more autonomous. Some of these solutions are aligned with specific vertical industries like manufacturing, insurance, or logistics, while others focus on specific functions within an enterprise, such as software development or marketing.

We have over 40 such active investments today, and another 40 seed (smaller) investments in younger companies. I have rarely been as excited about the potential that these companies have to make an impact and succeed throughout my career.

DM: Can you share an example of a recent investment that particularly excites you and why you believe it has strong potential?

EB: There are many I could choose, but I will pick one whose solution is easy to understand. One of our companies from our 4th early-stage fund is using AI to analyze satellite imagery. This type of data is far more plentiful and of high quality than it was about 5 years ago. There are now over 7000 LEO (Low Earth Orbit) satellites circumnavigating the earth and their image definition is now under 12 inches . This company – called AIDash – uses AI to model and understand in quasi real time vegetation growth and the risks of encroachment of vegetation into physical assets. As you know in California, particularly since the acceleration of climate change, we use several hundred thousand acres of forest every year due to forest fires. Most forest fires are caused by a tree that knocks down a high voltage powerline in a dry weather. AIDash is able to accurately pinpoint where such risks exist and use its findings in the workflows that dispatch forest maintenance trucks. In this way, these workers will go trim the trees that present a clear danger and not waste time patrolling routine routes with no interest. This will result in a far better utilization of resources within energy companies, telecom companies, or any enterprise with a vast far-flung physical infrastructure to manage and protect. We invested in AIDash very early, when it had its first AI model and its first product. It was about 3 years ago. We expect this young company to cross $20M in revenues this year. To put this in perspective, my first company Bridge Communications reached $20M in 1984, this is when we started to make plans to go public on Nasdaq …

DM: How do you see the role of venture capital evolving in the tech industry over the next decade?

EB: This decade (we are in 2024) is starting with a hard reset. The last couple of years since our emergence out of the Covid hiatus have seen the most vertiginous decline in VC activity, investments, valuations, exits, of the 21st century. The peaks reached in late 2021 were stratospheric. So, the fall from there feels that much more precipitous. I expect many firms to be unable to survive this nuclear winter. In 2010, there were just under 1,000 independent venture firms in the US. Today, there are over 4,000. While there are probably more good ideas that deserve to be funded today compared to 15 years ago, there are not enough to support the presence of this large number of firms. A “right-sizing” transition is inevitable, and I would argue, healthy. It takes a while for a venture firm to disappear. Venture funds are 10-year vehicles. Firms become zombies before they eventually collapse. We will have to navigate through this turbulence until a new point of equilibrium is found. I remain optimistic about our industry, and I am certainly very optimistic about the prospect for our firm BGV. But I admit that it is not for the faint of heart. In French, we still use the phrase “capital risque”. The notion of risk is integral to what we do, and it implies tall peaks and deep valleys.

DM: Now, let’s go on the lighter, unusual side with some “silly” questions, a trademark of my interviews. :) If you could have dinner with any historical figure, who would it be and why?

EB: From my teen-age years, I have been fascinated by David Ben Gurion, the pioneering founder of the state of Israel. He led a group of risk-takers and idealists to create a nation in a very hostile environment. This nation became start-up nation and epitomized the entrepreneurship experience. I have a special relationship with this man whom I never met. Ben Gurion University of the Negev is one of the top research universities in Israel. I served on the board of this university for about 15 years, received an honorary doctorate from its faculty, and taught there for a while. I founded a technology incubator in their Engineering School, which is just a few miles away from David Ben Gurion’s home in the Negev desert. Like everyone, while he showed great leadership, he also made a few mistakes that Israel is paying for today, such as cutting a deal with the ultra-religious minority (tiny at the time) and allowing them to shirk the duties of building the country. I would love to have him tell me what he would have done if he could revisit this decision, after seeing how it played out.

DM: What's the most unusual item on your desk right now?

EB: On the coffee table next to my desk, is a module of the Whirlwind computer built by Jay Forrester from MIT for the US Navy in the 1940’s. It is a 5-pound slide-in module full of vacuum tubes, resistors and capacitors. It was gifted to me in 1995. At the time, there was a televised computer trivia game called the Computer Bowl, opposing an East coast team to a West coast team. The West coast team won. Our prize was a module of this ancestral computer. Many young people who come to visit my office have no idea that this was state of the art technology in the aftermath of World War II.

DM: If you could instantly learn any skill or talent, what would it be?

EB: I have been fond of playing the guitar since I was a teen-ager. To this day, I have about 10 guitars in my home, some folk guitars, a classical Spanish guitar, an electric jazz guitar. I don’t play with a band anymore (I did when I was a student), but I enjoy playing classical guitar (J.S. Back, Albeniz, Sor, etc..). I still have decent mobility in my fingers, but I wish I could experience what professional players can create with their instrument.

DM: What's the funniest or most surprising thing that's ever happened to you during a business meeting?

EB: In 1988, 3Com had a strategic relationship with Microsoft. The champion of this relationship at Microsoft was Steve Ballmer. He came down from Redmond to visit me in Santa Clara. At the time, Microsoft was obsessed with their competition with Novell. They viewed 3Com as an ally in that holy war. At some point in the meeting, Steve became so passionate in his rant about killing Novell and wiping Netware from the face of the earth that he took out one of his shoes and started pounding our board room table with stupendous energy. This scene reminded me of Nikita Krutchev pounding the lectern with his shoe when he was addressing the United Nations assembly. The passion that invaded both characters (Krutchev and Ballmer) was not an act. It came out of every fiber of their being. I was stunned. I am a driven competitor as well, but I never exude emotions in the way that Steve is able to.

DM: If you could swap lives with anyone for a day, who would it be and what would you do?

EB: This is not a question that I ever thought about, but what comes to mind is the following: along the waterfront in Lisbon, Portugal, there is a large monument representing the age of the discoverers. Prince Henry is forward, with an arm extended pointing west. The others are famous discoverers like Vasco de Gama. (I don’t think Columbus is there ..). But I identify with this group of individuals, all driven by their passion to explore and not afraid of the distance and the risk. I would swap lives with any one of them, but only for a day.

Photo Source: The Objective Standard.

DM: Thank you so much, Eric, for sharing so many personal and intimate moments from your career and life. It’s truly a pleasure to see you not only keeping an eye on (and investing in) the latest technologies but also focusing on companies you genuinely care about. Interestingly, it seems that many tech legends in Silicon Valley found their way into technology somewhat by accident. Their core backgrounds often involved sciences, physics, mathematics, and a deep love for musical instruments. Maybe it’s time to think about a new curriculum for learning tech entrepreneurship that centers around these passions.